He never asked me my name, where I was from, what I do for a living. He took me at face value, simply accepted me for who I presented myself to be. I met him in a little bar at the corner of Avenida 20 de Noviembre where it runs into the Zocolo, just across the street from the National Palace. I was a hombre de Chicago on vacation. He was anyone you wanted him to be, nondescript other than for the t-shirt he wore, Che Vive! emblazoned across the chest.

I was waiting for my wife, busy blistering the Amex Card two neighborhoods south at the fashionable Polonca area, shopping on Calle Presidente Masaryk where the stores were upper- crust and featured catwalk knockoffs rather than the arts and crafts of the Bazaar Sabado, where I said goodbye after bearing up for as long as a bored husband had to endure before being dismissed with a kiss and a plan to meet later at the hotel.

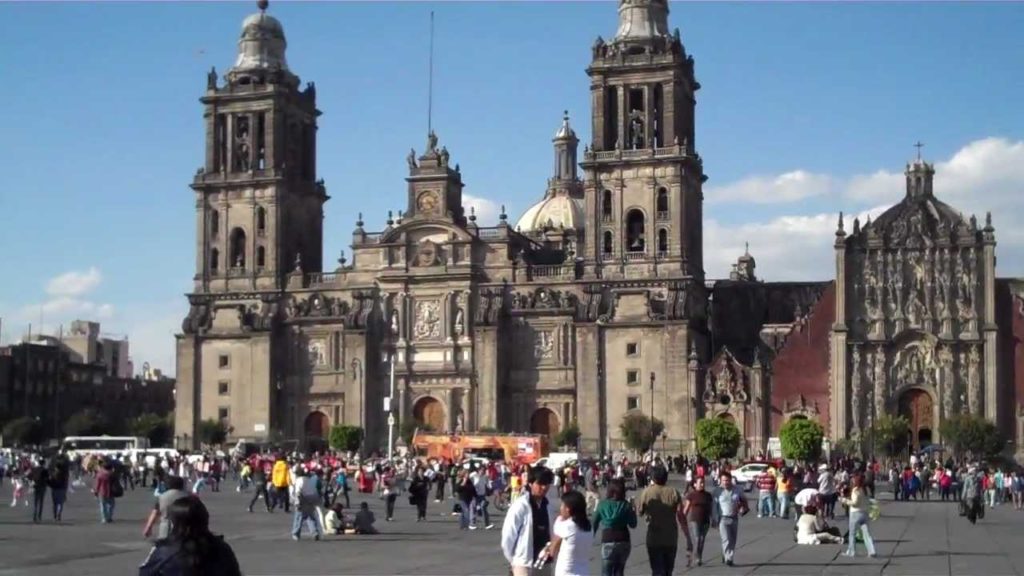

He was idling away the time as well, waiting for the start of a protest demanding greater democracy and rights for indigenous Indians scheduled in front of the old cathedral on the northern side of the square. The importance of his role in the event I learned later that afternoon.

Ordinarily, the Zocolo is a lively place where outdoor stalls selling everything from shoe polish to comals for frying tortillas compete for space with gawking tourists, strolling couples, Indian dancers, and long lines of families wanting to baptize their new babies. But this day was different; the impending demonstration had created a somber air of expectation that put a chill on frivolity as compelling as the October dampness defying the mid-morning sun. There was serious anarchy in the air, revolucion, ghosts of heroes past. The mood in the bar reflected the scene outside, the two us teetering on our stools, self-consciously sipping tequilas in lieu of black coffee.

That I was there was even more out of the ordinary, the trauma of 9/11, only weeks in the past having left most Americans too paranoid to leave their hometown, never mind go gringo south of the border. But our trip to Mexico had been planned and paid for months in advance when my Medicare card arrived along with my 65th birthday. “See Mexico” was at the top of the bucket list and we decided to keep our reservations despite the country’s apprehension. So the man in the Che Guevara t-shirt and I started to talk, strangers breaking the ice with the usual idle gossip that quickly grew more buoyant.

My new acquaintance had a plainspoken way about him that encouraged confidence, and I found myself responding freely, the anonymity of the encounter emboldening me. I didn’t hold back when he asked, curiously, “Le gusta Bush?”

I had been cautioned about talking politics, particularly to strangers, and until then, had made it a point to tip-toe around any conversation involving George W. or Vincente Fox, excluding a sarcastic comparison of their fancy hand-tooled cowboy boots which may have added to their height but did little to validate their People Magazine faux images as hard working vaqueros.

Perhaps it was the tequilas before noon that unhinged my semi-borracho tongue. “No! El es el presidente mas malo in la historia de los estados.” The unexpected vehemence of my reply was a surprise but obviously didn’t displease him. He took a surreptitious look around the bar, pulled his stool closer to mine, and launched into a litany not normally found on the course notes of a political science teacher interested in keeping his ass from being hauled in front of a PTA lynch mob.

“Democracy is bullshit,” he began. “In your country’s schools, you’re taught ‘Of the people, by the people, and for the people, but that’s… how do you say it literally, excrement del toro. In America,” he continued, “so-called democracy is a political system that serves only the minority of the people who seek power.” His passion grew in intensity, ranging from a denunciation of Wall Street to a condemnation of “an immoral society that feeds scraps to a helpless underprivileged stratum of society while gorging itself on arbitrage that produces illicit profits for the top one half of one percent of the population.” If his logic was short of impeccable, his fervor was undeniable. “Who will fight for the rights of the forgotten people?” he trumpeted. “¿Quién lucha por los derechos de los indios?”

“I will!” I shouted spontaneously, intuitively anticipating my part in the rebellious call and response chant that soon would ricochet off the ancient buildings surrounding the city’s sacred plaza.

I paid for another round of Jimador Blanco, tuition for a lesson in regime brutality that began in Chiapas in the early nineties, where the flamboyant Subcomandante Marcos – poet-philosopher, pipe-smoking, ski mask-wearing champion of the downtrodden – had mobilized the Zapatista National Liberation Army to petition for the rights of the Indians. It was there, in the village of Acteal, where a group of paramilitaries tied to the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) attacked a prayer meeting and massacred 45 villagers, including children as young as two months old. The resultant outrage made the headlines for the customary fifteen minutes of attention, curiosity over the identity of the mysterious Marcos overriding the movement’s desperate struggle for human rights. It took four years of agitation to cloak the Zapatistas in semi-respectability and force the reluctant regime of newly elected Vincente Fox to pay lip service to the continuing abuse of the region’s indigenous peoples.

The afternoon’s demonstration about to take place in the Zocolo was the culmination of a month-long, bus caravan tour of Mexico to call attention to the region’s desperate need for roads, health clinics, schools and electrification projects in the mountainous backcountry where the descendents of the Mayans lived.

My empathy for the movement and unexpected familiarity with the 1994 free-trade agreement that had driven prices for corn and beans brutally low for the farmers in Oaxaca, surprised and impressed my new amigo. (I smugly neglected to mention I was parroting the reporting in the NY Times, delivered to my home every morning). “The indigenous people are living in an abysmally precarious state, with virtually nothing that we would call a humane, dignified, modern developed life,” I held forth from the soap box, speechifying in a slurred Spanglish.

My friend slapped me on the back in approval and set off on another flight of impassioned rhetoric. The goal, he posited, was to push mainstream politicians to the left rather than trying to consolidate rebel territory or improve agricultural output. His idea was to recruit unionists, radicals, and community groups to carry out “a national leftist, anti-capitalist program leading to a new constitution, which is another way of saying a new agreement for a new society.”

Suddenly I blurted like an awed groupie, “You are Marcos!”

The realization as to whom I was talking left me bowed in deference to the rebel leader, a heroic Emiliano Zapata resurrected to lead his people anew. I was sure this was the man the government had identified in 1995 as Rafael Sebastian Guillen, a former university instructor with no history of a traffic ticket, never mind incendiary rabble rousing and a call to outright sedition.

“Not that big a fish,” he laughed, steering me away from questions about his personal life and whether he was, in fact, the movement’s military leader, not its “assistant commander,” as he had maintained.

Outside the bar, hundreds of people began to pour out of the Metro station located at the northeast corner of the square. The demonstration would soon begin. If he was the mysterious Marcos, I would never truly know; it was time to join the crowd.

As we exited the bar, my friend transformed before my eyes, a Marvel Comics plotline, from mild-mannered everyman to bigger-than-life superhero, his mien more determined, his stature altered – how can a man suddenly grow several inches taller? – his eyes holding bystanders in thrall like laser beams from a sniper’s range finder. Soon they would glow just as brightly from behind the black ski mask he pulled out of his backpack. Impulsively, he stopped and turned to me.

“You are a natural born revolutionary, un luchador por los pobres, a fighter for the poor.” His words were marching orders. Grasping me by the shoulders, he commanded, “Speak for the downtrodden, mi viejo guerrero, my old warrior. Speak for the people without voices!”

The photograph that appeared on the front page of the newspaper El Reforma documented what occurred next. You can see me on the platform in front of the cathedral standing next to the man who might or might not have been Marcos. I am leading the chant that is turning the crowd into an army of righteous libertarians: El poder al pueble (power to the people). Larga vida a Marcos (long live Marcos)! The picture in the newspaper was taken from some distance away but clearly I stood out as a leader among the swarm of dissenters exhorting the crowd. I too seem to have grown several inches taller.

I met my wife at the hotel in the late afternoon, a battered jeep dropping me off at the Nikko amidst a chorus of “Vaya con dios viejo guerrero (Go with god old warrior).”

“Where were you?” my wife asked, askance. “You look like a steamroller flattened you.”

“It did,” I replied.

The fading light, filtered by the city’s smog, poured softly into the elegant suite. A tall glass of water poured from a chilled bottle of Vilas del Turbon helped do away with the last of the morning’s binge. I took a relaxing hot shower, hid my mask in the laundry bag, and dressed for dinner without further explanation.

“Mr. Whitney, your three o’clock is here.”

The corner office I still retain on the top floor of Lake Forest’s tallest office building is an impressive place to do business. The clients who come in to negotiate multi-million dollar policies insuring seasonal inventories, half-built condominiums, and over-hyped entrepreneurial schemes are reassured by the cherry wood conference table and Herman Miller chairs that speak to the success of Pierce Whitney II and Associates. I was the third generation Whitney to run the business, arriving promptly at nine each morning impeccably dressed in Marc Shale suits and given to colorful Hermes ties on the brink of affectation, my feigned smile hiding a enduring bitterness at having been selected for the job. I can’t deny I had a choice; I knew full well the difference between living the good life and being a good man.

On Christmas Eves past, I was a member of the church volunteers serving dinner to the homeless. My heart was opened wholly, flooded in love for my fellow man. I saw past the layers of grime, the toothless grins as served and server joined in grace. In return for two hours of selflessness, I received a sense of bliss that money could not buy.

After high school I had decided to become an artist, defying my father’s anger by applying to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago rather than the “more selective” Amherst College, where father and grandfather did little to enhance the school’s academic reputation but led the Lord Jeffs to consecutive “little three” football titles versus arch rivals Williams and Wesleyan.

Upon graduating, I joined the army rather than face the family’s disdain for my “useless” BFA and spent eighteen months slogging up the Korean peninsula, exposed to a world where privilege meant bringing up the rear while on patrol instead of taking the point and facing the prospect of stepping on a Soviet POMZ fragmentation bomb or one of our own M14 anti-personnel mines the army scattered around the country like cow patties.

When I returned home, I rented an apartment in Chicago for six months of silk sheets, mai tais, and Hong Kong steaks at Jimmy Wong’s, front row tables for the Myrna Loy show at the Blackstone Theater, and a membership in the Drake Hotel’s private Club International.

When my father finally stepped in and forced me to confront a future expelled from the trust fund I had come to know and love, my argument for “artistic expression” and a small studio on South Halsted Street had lost its luster. The sirens sang their songs. The opulent reminders of what money could buy, a Pate Philippe watch, a summer traveling around Europe, a fire engine red MG-TD, proved irresistible

On cue, my appointment paused in front of the row of photographs hung conspicuously on the wall of my office, the autographed glossies of Rush Limbaugh and Dick Cheney and similarly smug and thin-lipped mainstays of the Grand Old Party speaking to the firm’s insouciant disregard for clientele lacking the appropriate blue blood or greenbacks. Updated from the original black and whites of my father posing proudly with Ford and Reagan – his autographed photo of Richard Nixon banished to the back of the file case after Watergate – the gallery follows my receding hairline to the most recent eight-by-ten of a golf foursome with an obviously sloshed Mike Ditka, 10th district Representative Mark Kirk, and former governor Big Jim Thompson. The yellowing photograph that appeared on the front page of the Reforma is not to be seen, not even behind the ficus tree in the corner of the office, where a gag shot of me on the cover of Mad Magazine raised quizzical uplifted eyebrows among Lake County’s ruling class elite.

That picture of “the crazy masked guys,” as my wife described it, was as closeted as my donation to the Obama campaign.

What would my masked friend have thought of me had he seen me at work in my fancy office, hob-nobbing with the cake eaters while the price of tortillas became ever more onerous? What would he think of my mini-mansion in Lake Forest, one of the most affluent communities in the United States, with a Latino population of 0.87% – the town’s manicured lawns and well-trimmed shrubs providing explanation for 174 undocumented Mexican families living within three blocks of each other on the side of town abutting the Metra train switch yard and sanitation plant? Would he choke on the cynicism of practicing Spanish with Mariano Ochoa, he of the Ochoa Landscaping Company, the contractor that mows our lawn every Saturday morning for twenty-five US dollars paid in cash, no receipt necessary? I wonder if he has softened his observations about the viability of democracy considering the election miracle of 2008.

As for me, the secret fire of radicalism I concealed even as I partied with the Young Republicans and turned my back to the plantation politics of privileged Wasp friends has been extinguished. I never blew my cover. I never clinked my glass and stood tall to speak to the rights of the underclass, the disenfranchised, America’s own downtrodden indios. It’s too late now for the impassioned speech. When beliefs and feelings are kept hidden, out of the light they become more quarrelsome than well argued, wizened by their betrayal, rendered lifeless by having been left unspoken.

I see my reflection in the mirror of the office’s restroom. I am wearing a mask more opaque than the blackest wool ski mask of Marcos himself.